Theme

Simulation and Simulated Patients

Category

Simulated Patients

INSTITUTION

Center for Innovation in Medical and Dental Education, Kagoshima University

In our study, using the instruments of CI, which have equivalent items but are expressed as observable behaviors for faculty raters and SPs, paired scores of the same examinees showed a discrepancy at item levels. Those scores were rarely identical or showed positive correlations, especially for the items of listening and understanding the patients, expressing empathy, and global rating of an examinee as a medical graduate.

For the assessment of communication and interpersonal skills (CI) of medical students and residents, scores of checklists rated by physicians and SPs have been discussed regarding whether they reflect competency and patient s’ perspectives (ref. 1-8). In our previous study, total scores for CI by faculty raters (physicians) and SPs were weakly correlated, but the different perspectives of both were not clearly identified.

Fifteen SP cases in OSCE encountered by sixth-year medical students at Kagoshima University in 2010 and 2011 were analyzed. Faculty raters scored the CI as well as history taking (content), physical examination, informing of diagnosis and plan for SPs in the examination room. After 20 minutes, SPs scored CI in the SP rating room.

.jpg)

Five items of listening (L), five of explaining and decision-making (ED), and 4 of attitude and the whole process (AW) were scored by a faculty rater and an SP for each examinee using equivalent instruments (see Details). Scores were analyzed using the Pearson correlation coefficient and paired t-test.

Faculty and SP raters have different perspectives on CI, and do not complement each other.

The authors thank the sixth-year medical students, faculty members, Kagoshima SP group members, and staff who participated in the OSCE and this research.

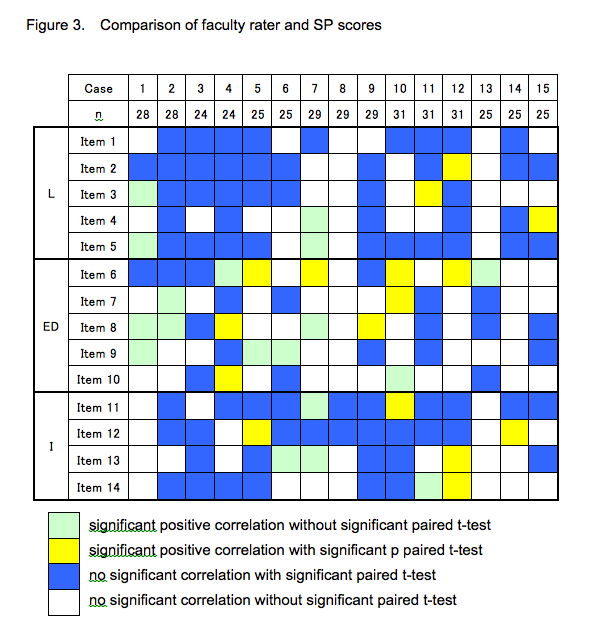

1. Items showed a positive correlation between faculty and SP scores by the Pearson correlation coefficient (p<0.05) were 34 among 14 items of 15 cases (16 %).

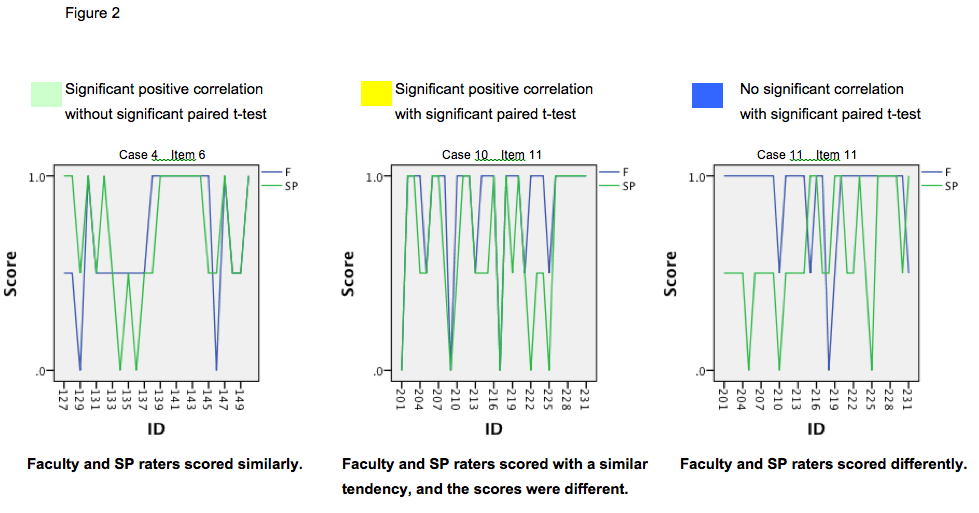

2. We classified items into psychometric criteria (Figure 2), and each item’s psychometric property of each case is shown in Figure 3.

Significant score differences were detected for items of listening behaviors and understanding the patients (Items 1, 2, and 5), expressing empathy (Item 11), and examinee’s attitude such as enthusiasm and confidence for the medical students expecting graduation (Item 12).

- Stiles WB. Evaluating medical interview process components. Null correlations with outcomes may be misleading. Med Care. 1989;27:212-20.

- Martin JA, Reznick RK, Rothman A, Tamblyn RM, Regehr G. Who should rate candidates ina an objective structured clinical examination? Acad Med 1996;71:170-5.

- Zoppi K, Epstein RM. Is communication a skill? Communication behaviors and being in relation. Fam Med 2002;34:319–24.

- Thistlethwaite J. Simulated patient versus clinician marking of doctors’ performance: which is more accurate? Med Educ 2004;38:456.

- Egener B, Cle-Kelly K. Satisfying the patient, but failing the test. Acad Med 2004;79:508-10.

- Mazor KM, Ockene JK, Jane Rogers H, Carlin KM, Quirk ME. The relationship between checklist scores on communication OSCE and analogue patients’ perceptions of communication. Adv Health Sci Educ 2005;10:37-51.

- Makoul G, Krupat E, Chang C-H. Measureing patient views of physician communication skills: Development and testing ot the communication assessment tool. Patient Educ Couns 2007;67:333-42.

- Salmon P, Young B. Creativity in clinical communication: from communication skills to skilled communication. Med Educ 2011;45:217-26.

- Boon H, Stewart M. Patient-physician communication assessment instruments: 1986 to 1996 in review. Patinet Educ Couns 1998;35:161-176.

- Duffy FD, Gordon GH, Whelan G, Cole-Kelly K, Frankel R. Assessing vome@tence in communication and interpersonal skills: The Kalamazoo II Report. Acad Med 2004;79:495-507.

- Schirmer JM, Mauksch L, Land F, Marvel K, Zoppi K, Epstein RM, Brock D, Pryzbyiski M. Assessing communication competence: a review of current tools. Fam Med 2005;37:184-92.

- Rider EA, Keefer CH. Communication skills competencies: definitions and a teaching toolbox. Med Educ 2006;40:624-9.

- Iramaneerat C, Myford CM, Yudkowsky R, Lowestein T. Evaluation the effectiveness of rating instruments for a communication skills assessment of medical residents. Adv Health Sci Educ 2009;14:575-94.

- Huntley CD, Salmon P, Fisher PL, Fletcher I, Young B. LUCAS: a theoretically informed instrument to assess clinical communication in objective structured clinical examinations. Med Educ 2012;46:267-76.

Send Email

Send Email