Theme

9AA Teaching and assessing communication skills

INSTITUTION

Jagiellonian University Medical College - Department of Medical Education - Kraków - Poland

This academic year (2014/2015) we have introduced a course in Clinical Communication, based on simulation and role-playing, for students of our faculty. The course runs at the beginning of the third year of studies, in parallel with clinical introductions to internal medicine, paediatrics and surgery, and complements their content in the area of history taking and basics of patient counselling. We were curious of students’ attitudes towards the course content and format, which is totally new in Poland.

At the end of the course in Clinical Communication, students were asked to fill in a questionnaire, anonymously. The questionnaire included a student satisfaction test, assessed by a Likert-type five point scale, and open-ended questions about areas for possible improvement. The results were collected and analysed using descriptive statistics and a Spearman’s rank correlation.

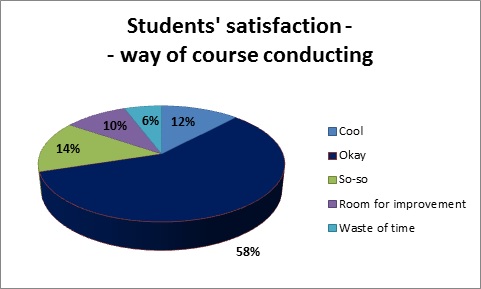

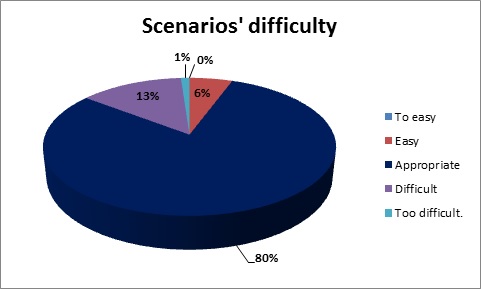

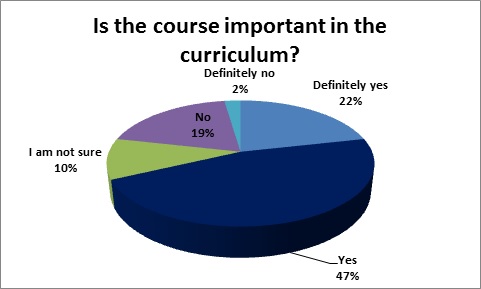

We collected a total number of 179 answers from students of the third year of medical studies (return ratio 83%). Student satisfaction during the course was high: 70% of the students liked the way, in which the course was conducted; in 12% of the cases our course scored the highest mark, whilst in 6% of the cases it scored the worst one (Fig. 1). Answers correlate with perception of the quality of the course (Spearman’s rank 0,61; p<0,000001) and additional materials (Spearman’s rank 0,36; p<0,000001). By 80% of the students the difficulty level of the scenarios was perceived as appropriate (Fig. 2). 62% of the respondents considered that the course is important or very important in the curriculum (Fig. 3). Students indicated some technical areas for improvement and very precisely identified more difficult topics, which should be addressed in the future teaching.

Fig. 1 Students’ opinion about the way, in which the course was conducted.

Fig. 2 Difficulty of scenarios.

Fig. 3 Importance in curriculum

A majority of the students was satisfied with our approach. Further development of the course requires reflection over cultural factors specific for Polish conditions. Good coordination with clinical classes is essential. In our case this goal is realised mainly throughout OSCE exam, which is common for all clinical introductory subjects.

Bosse, H.M. et al., 2012. The effect of using standardized patients or peer role play on ratings of undergraduate communication training: A randomized controlled trial. Patient Education and Counseling, 87(3), pp.300–306.

Koponen, J., Pyörälä, E. & Isotalus, P., 2012. Comparing three experiential learning methods and their effect on medical students’ attitudes to learning communication skills. Medical Teacher, 34(3), pp.e198–e207.

Kurtz, S., Silverman, J. & J, D., 1998. Teaching and Learning Communication Skills in Medicine., Oxford, UK: Radcliffe Medical Press.

Luttenberger, K. et al., 2014. From board to bedside - training the communication competences of medical students with role plays. BMC medical education, 14(1), p.135. Available at: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6920/14/135.

Silverman, J., Kurtz, S. & Draper, J., 2005. Skills for communicating with patients, Oxford, UK: Radcliffe Medical Press.

Send Email

Send Email